Fragments of

Carcosa:

The Marie Vigée Collection

Lots 1-28

Strange is the night where black stars rise,

And strange moons circle through the skies,

But stranger still is

Lost Carcosa.

Songs that the Hyades shall sing,

Where flap the tatters of the King,

Must die unheard in

Dim Carcosa.

Curated by Marie Vigée’s daughter Lili, these 28 artifacts include sculptures, jewelry, specimens, and works of decorative art. They are, in Lili’s words, “the summation of my mother’s exquisite taste, and a glimpse of her obsession.”

Piermont & Thorne has no official policy concerning the reality of Carcosa.

Summer, 1995

The Grande Plage, Biarritz. (Wikimedia Commons)

In the summer of 1995, between my junior and senior year of college, Jimmy Rockland introduced me to Marie Vigée. I’d talked my way into a summer writers residency in Biarritz, which required I show up at the local bookstore every week or so to read a few pages from my soon-to-be-discarded novel about a failed painter, in exchange for an elegant two-bedroom within shouting distance of the beach. I was proud of my theft—a victimless crime, the owner of the apartment kept it vacant ten months out of the year and was grateful for someone to check up on the place—and I knew, rightly so, that I would never again receive so much in exchange for so little.

One day during my fourth week I was sitting at Jimmy’s bar drinking my usual drink (an Americano, made of equal parts Campari and sweet vermouth, topped with sparkling water) when Jimmy slid me a refreshed bowl of peanuts and suggested, apropos of nothing, that I introduce myself to a local resident named Marie Vigée.

“I bet she could help you with your book,” he said.

“I don’t need help,” I said.

“I meant with research,” he said. Jimmy, like many non-writers, believed research was one of the bigger obstacles.

“She’s incredibly well-connected,” he continued. “She knows everyone. And I mean everyone.”

Add Marie Vigée to Jimmy’s pantheon: Charles Saatchi, Salman Rushdie, Martin Amis, Lou Reed, V.S. Naipaul, Truman Capote, Gunter Sachs, Bianca Jagger, Baron Hans Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza. As proof of his associations Jimmy hung their pictures behind the bar, photos of them posing with Jimmy, arms over shoulders, mouths wide, drinks spilling, shirts unbuttoned.

“I’ll call next time she’s coming in,” he said. “Wear a decent shirt.”

Tennis in the Bahamas, circa 1957, photograph by Slim Aarons. Marie Vigée is the young woman in white, her face partially hidden by her hat. She was nineteen at the time of this photograph.

A few days later Jimmy telephoned to say that Marie made a dinner reservation for that night, sans Mr. Vigée who was bedridden with gout. I put on a decent shirt and bicycled to the bar where I found Marie seated alone at the biggest table by the biggest window, eating her favorite meal: a plate of naked spring greens, an unsalted soft pretzel, and a champagne flute of club soda and fresh blackberry juice. She looked to be about fifty, tall and cool and slim, with ash-blonde hair cut in a French bob. She wore tailored jeans, a striped oxford untucked and rolled to the elbows, a Cartier watch, a pearl choker. I introduced myself and she invited me to sit.

“James tells me you’re a writer,” she said.

“I’m working on a novel,” I said.

She sipped her drink. “Seems everyone is working on a novel. James was working on a novel a few years back.”

“Memoir,” Jimmy shouted from behind the bar. “But nobody will sign a release form to publish their photos. Ungrateful bastards. Except for you.”

She smiled at me. “And what is your novel about?”

I explained as best I could: the failed painter, the alienated family, the drinking, the drugs, the fickle gallery owners, the cruel critics. She listened patiently, then said I wouldn’t learn anything from artist biographies or memoirs—I needed to insert myself into their world. We spoke until closing and finished several bottles of wine. Jimmy was right: I fell in love. When I returned home to upstate New York I abandoned my novel but my education with Marie continued. She introduced me to some of the world’s top collectors of art and antiquities, all of whom I pretended I needed for research; truth was I just wanted to be around Marie.

After graduation Marie invited me to stay in her Paris pied-à-terre, a small two-bedroom in the 3rd arrondissement. She apologized for the clutter. She said her collection had doubled in two years and the apartment was now serving as her warehouse. What Marie called “clutter” remains one of the foremost assemblages of European paintings from the Renaissance to the late 19th century, including works by Jan van Eyck, Caravaggio, Rembrandt, and Claude Monet.

Marie also had a fascination with the occult, specializing in holy relics, rare grimoires, and boxes that allegedly held demons. “I don’t believe demons exist,” she confessed to me. “At least not in the traditional sense. But I do believe there are evil entities who extend their influence into our world.”

The most surprising part of her collection were the dozens of artifacts from the fabled city of Carcosa. While many assume Carcosa to be the literary invention of Ambrose Bierce, Marie insisted Carcosa was akin to Atlantis, Agartha, and other lost civilizations. She insisted she knew explorers who had visited its strange land and brought back proof.

To date there is no means of confirming the origins of these beautiful objects. Still: I believe if Marie Vigée believed. Like all great collectors, Marie’s personality is evident in the objects she valued, and in curating these pieces I felt reunited with her. I thank you for joining Piermont & Thorne in this exploration of Carcosa, with the incomparable Marie Vigée as our guide.

Happy Bidding,

Micah

Along the shore the cloud waves break,

The twin suns sink behind the lake,

The shadows lengthen

In Carcosa.

Strange is the night where black stars rise,

And strange moons circle through the skies,

But stranger still is

Lost Carcosa.

Songs that the Hyades shall sing,

Where flap the tatters of the King,

Must die unheard in

Dim Carcosa.

Song of my soul, my voice is dead,

Die thou, unsung, as tears unshed

Shall dry and die in

Lost Carcosa.

- “Cassilda’s Song,” The King in Yellow

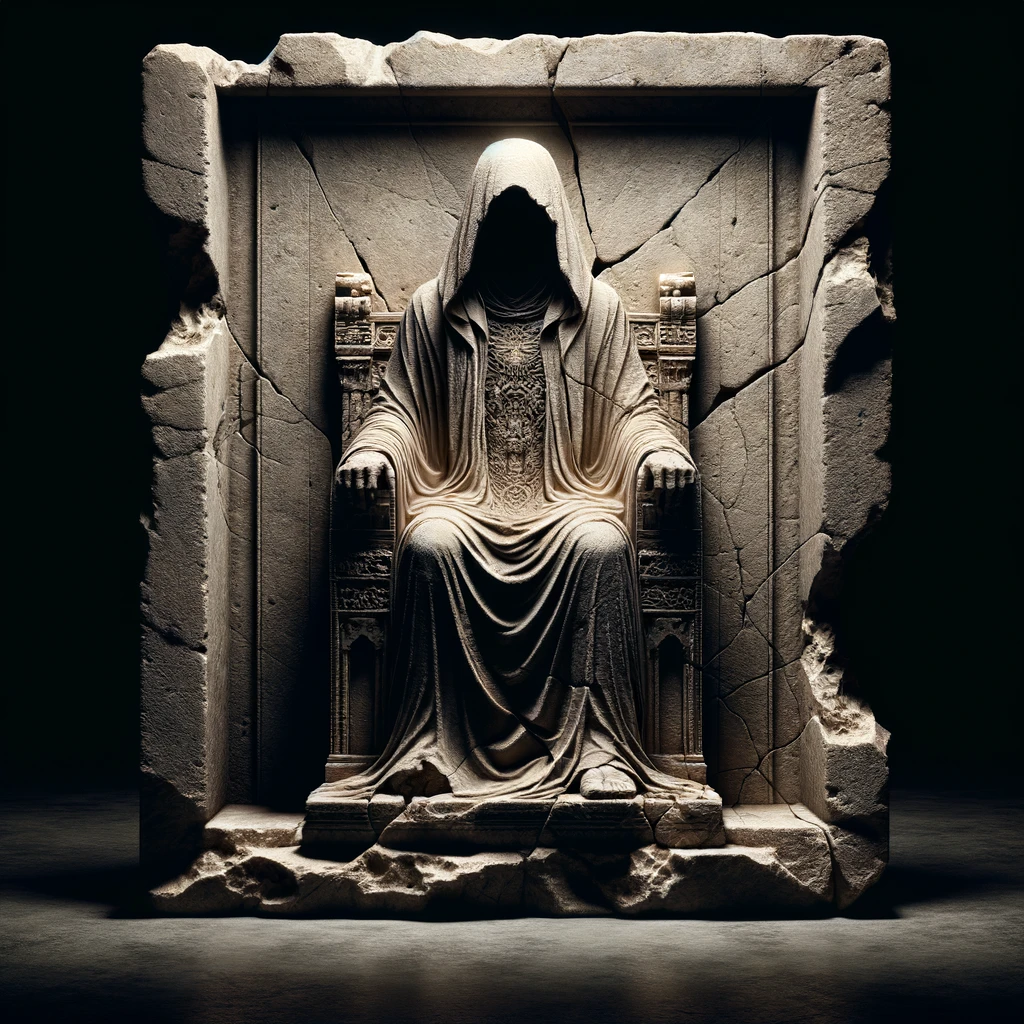

A sandstone sculpture retrieved from the ruins outside Carcosa’s city walls. In private collection.

In 1925 the Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung wrote about a series of dreams in which he traveled to a city “with nothing familiar about it and yet I felt I had been there before.” He spent hours wandering its streets, seeing no one else but feeling watched, in particular by “the reliefs carved into almost every building, often of the same hooded figure with little variation, whose face remained hidden in darkness.” Carvings at the base of those reliefs bore the same name: The King in Yellow.

The dreams intensified to the point where Jung feared he was going mad; he felt as though the city were a riddle asking to be solved. He searched for meaning in the repetitions, what he described as “hundreds of variations on the same themes, the sculptures, reliefs, and idols all similar at first glance until further inspection revealed details whose differences seemed vital, though I cannot determine why.” His dream-wanderings brought him closer to the city gates beyond which he could see forested hills and a jade-colored sky, but the streets always led him away, back to the center, where a tall stone sculpture of the King in Yellow emerged from a well. Grotesque toads and lizards surrounded the well, refusing to move even as Jung walked among them.

Eventually the dreams stopped. “And yet I still catch glimpses of the King in Yellow,” he wrote in his journal. “That hooded figure lurking at the edges of my vision, who perhaps serves as a reminder of a terrible fate avoided.”

***

At seventeen years old, the French artist Gustave Doré (b.1832—d.1883) was stricken with a fever that lasted eight days. When he awoke from his delirium he told his parents about his travels through a strange city, accompanied by a silent, long-haired, bearded man. Mounds of bones—some human, others monstrous—spilled from nearly every street corner, and in the town square stood a tall statue of a hooded figure. Like Jung, Doré spoke of seeing toads and lizards surrounding the statue. Unlike Jung, Doré entered some of the city’s buildings.

“Aucune personne, mais de nombreux objets, certains assez vieux, d'autres contemporains,” he wrote to his cousin. No people, but many objects, some quite old, others contemporary. Doré mentioned furniture, clocks, cups, and objets de vertu, including grotesque figurines and toads carved from ivory. He said he stole a small skull from one of the many mounds but when he emerged from his fever the skull was gone; a year later he found the skull buried in a box in his closet, with no recollection of how it got there.

***

The Road to Carcosa, attributed to Gustave Doré, 1847. In private collection.

The American philosopher/theologian Francis Ellingwood Abbot (b.1836 — d.1903) recounted in a letter to William James “a most terrible and vivid dream.” In it, he was on the shore of a dark lake, behind him a city whose white spires stood against a night sky “bearing two moons, one large, one smaller.” Abbott wrote he was transfixed by “something roiling beneath the surface, lit by those twin moons, a monster the width of a whale but much longer. I feared it would rise up and snatch me from the shore, and yet I could not move. I believed it was Leviathan, and despite my terror I marveled.”

Hours passed and the monster eventually disappeared, but not before lifting its head out of the water. “It marked me,” Abbot wrote. “Its eyes glimmered green above a tentacled, writhing mass; the face of madness. Had it stared much longer, I daresay my mind would have broken. By God’s grace it sank below the surface.”

***

The Old Testament contains two possible references to Carcosa. Exodus 8:2-15 describes one of the plagues inflicted upon Egypt as a swarm of tsepharde'a, meaning a kind of frog or toad. The theologian Dr. Gordon Yates posits there is an account in the apocryphal text The Book of Plagues stating where the tsepharde'a originated, namely אגם חלי, which he translates as “Lake Hali.” He also points to Proverbs 30:28: "The lizard you can take in your hands, yet it is in kings' palaces." Dr. Yates believes Carcosa is among those palaces.

The city of Carcosa exists clearest of all in literary memory. Ambrose Bierce’s story “An Inhabitant of Carcosa,” published in 1886, follows an unnamed narrator who awakens on a desolate plain with no memory of how he arrived there. He discovers remnants of a civilization now reduced to ruins, covered in symbols that hint at an ancient city called Carcosa. Night falls and he wanders along the broken statues and megaliths, seeing no life other than an owl, a lynx, and eventually a man, “half naked, half clad in skins” who “broke into a barbarous chant in an unknown tongue, passing on and away.” The narrator rests near a tree and finds, entangled among its roots, a tombstone bearing his name, date of birth, and date of death. The story ends with narrator discovering he casts no shadow despite the sunrise, while in the distance he spots wolves “…on the summits of irregular mounds and tumuli filling a half of my desert prospect and extending to the horizon. And then I knew that these were ruins of the ancient and famous city of Carcosa.”

In 1895 Robert W. Chambers wrote a collection of stories titled The King in Yellow, revolving around an entity known as the King in Yellow, as well as the eponymous play, said to induce madness and despair in those who read it or witness its performance. In 1931 H.P. Lovecraft made reference to Lake Hali, on whose shores Carcosa stands.

Those are the well-known mentions of Carcosa, but there are others.

***

1. AN ANCIENT HIGH RELIEF CARVED LIMESTONE FIGURE, FROM THE WESTERN WALL OF THE TEMPLE...

2. AN ANCIENT HIGH RELIEF CARVED LIMESTONE FIGURE, FROM THE EASTERN WALL OF THE TEMPLE...

3. AN ANCIENT HIGH RELIEF CARVED LIMESTONE FIGURE, FROM THE SOUTHERN WALL OF THE TEMPLE...

4. AN ANCIENT BAS-RELIEF CARVED LIMESTONE FIGURE OF A SEA DEITY, UNKNOWN CENTURY

5. A CARVED YELLOW AGATE STANDING FIGURE, 18TH CENTURY

6. A CARVED BASALT BUST, 14TH CENTURY

7. A CARVED STONE MASK OF A YOUTH, 9TH CENTURY

8. A CARVED MARBLE MASK OF A YOUTH, 8TH CENTURY

9. A GLASS MASON JAR WITH WATER, SEDIMENT, AND ORGANIC MATERIAL FROM LAKE HALI, EARLY 20TH CENTURY

10. A CARVED JADE LIZARD FIGURINE, EARLY 18TH CENTURY

11. A CARVED DARK SPINACH JADE FROG FIGURINE, LATE 19TH CENTURY

12. A GROTESQUE CARVED IVORY TOAD FIGURINE, 18TH CENTURY

13. A CARVED ROSEWOOD TOAD FIGURINE, EARLY 18TH CENTURY

14. A CARVED SCORIA TOAD FIGURINE, LATE 19TH CENTURY

15. A GROTESQUE CARVED IVORY TOAD FIGURINE, 18TH CENTURY

16. AN EARLY BRONZE CELESTIAL GLOBE, LATE 17TH/EARLY 18TH CENTURY

17. A RAG PAPER CELESTIAL MAP LAID ON LINEN, 16TH/17TH CENTURY

18. A STERLING SILVER EWER, LIKELY MID-20TH CENTURY

19. PLAGUE OF TOADS, INDIA INK ON LINEN LAID ON PANEL, 17TH CENTURY

20. A CABOCHON GARNET AND LOW KARAT GOLD RING, LIKELY 14TH CENTURY

21. A CONTORTED BEAST WITH SELF-HELD HEAD, UNKNOWN CENTURY

22. A GROUP OF HOUSEHOLD ITEMS, LIKELY EARLY TO MID-20TH CENTURY

23. A CAST BRONZE FIGURE OF A SEA DEITY, LIKELY EARLY 17TH CENTURY

24. A DIAMOND AND 18 KARAT GOLD CROWN, LIKELY MID-16TH CENTURY

25. A HAND CARVED IN SANDSTONE, LATE 17TH CENTURY

26. A STERLING SILVER CAST, CHASED AND FILIGREE-DECORATED EGG, LATE 18TH CENTURY

27. A CARVED IVORY AND BLOWN GLASS MODEL OF A MAMMALIAN EYE, EARLY 19TH CENTURY